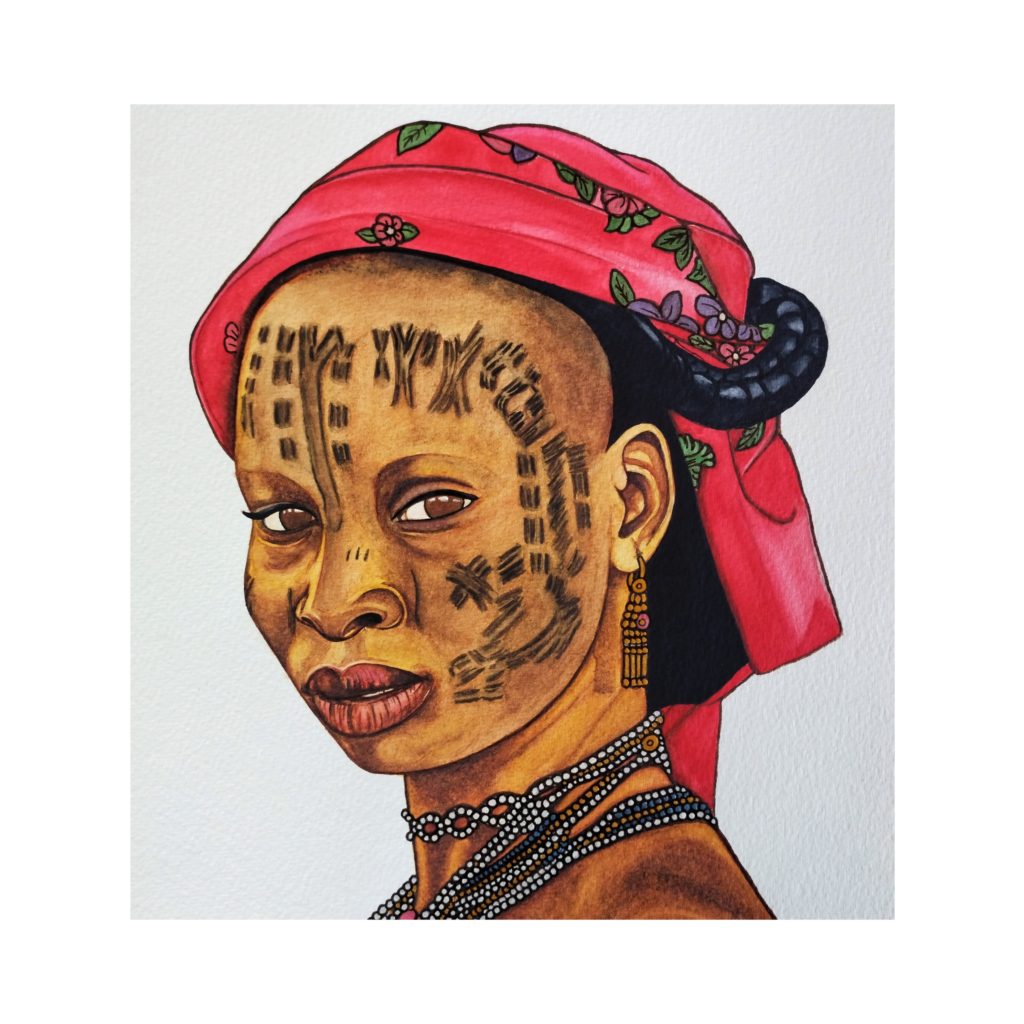

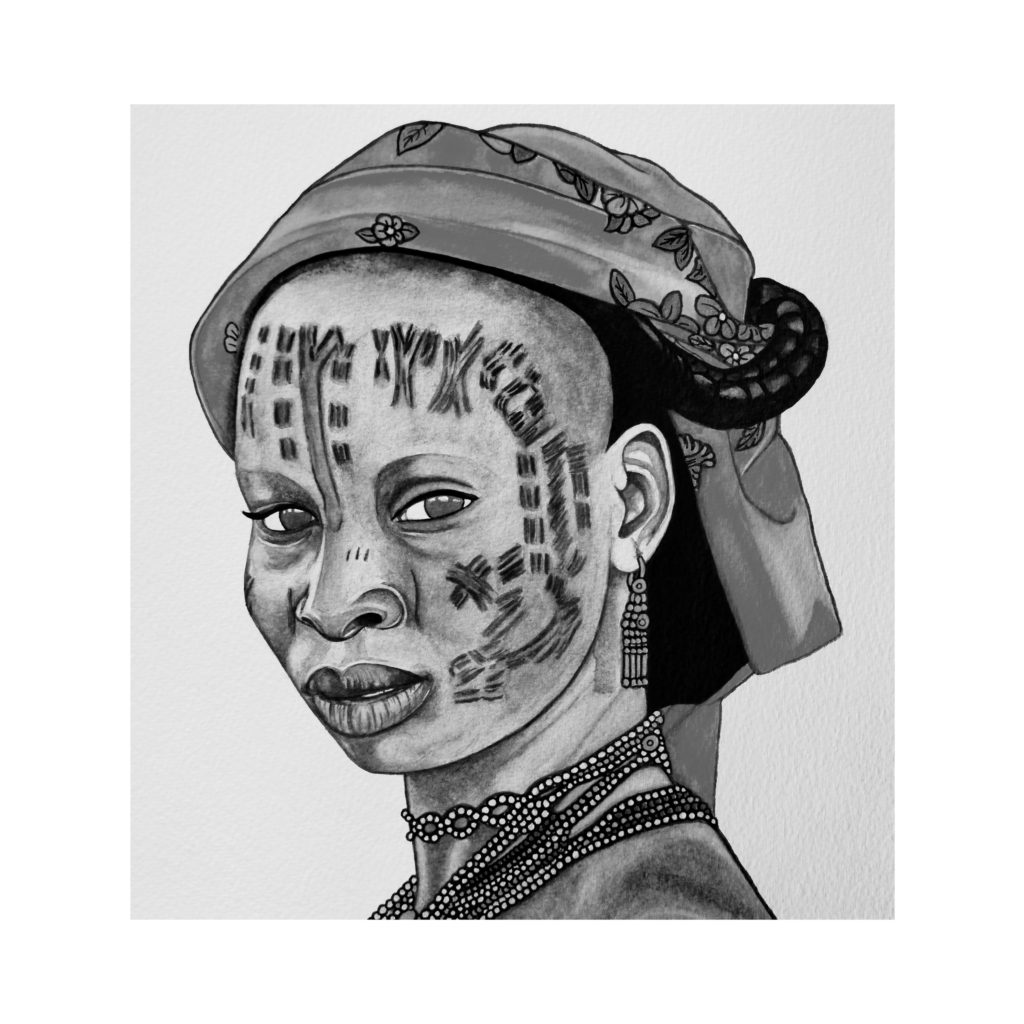

ACUARELA. Mujer con escarificación etnia Fulani. WHATERCOLOR. Woman Scarification of etnia Fulani . (Photo bank of imagen )

En el pueblo de Mbororo, ubicado en Chad en África central, vive una comunidad de alrededor de 250,000 miembros pertenecientes al grupo étnico Fulani. Los Fulani son un subgrupo nómada y animista que habita en África central y occidental, siendo uno de los grupos étnicos más grandes de este tipo en el mundo. La cultura de los Mbororo se destaca por su práctica de tatuajes y trenzado de cabello como expresiones estéticas.

La escarificación es una característica importante de la cultura africana en la que se crean diseños en relieve en la piel a través de cortes y la aplicación de cenizas vegetales u otros materiales. Estas prácticas pueden clasificarse en cuatro grupos: marcas tribales para diferenciar etnias, cicatrices masculinas para demostrar valor y virilidad, escarificaciones femeninas por motivos estéticos y eróticos, y para evitar enfermedades mediante curanderos.

En los Mbororo, la escarificación y el tatuaje son parte integral de su estilo de vida nómada y se han mantenido debido a su resistencia a influencias modernizadoras. Además, se menciona el grupo Wodaabe dentro de los Fulani, que ha mantenido sus tradiciones nómadas y culturales, incluyendo tatuajes y talismanes para atraer la buena suerte y la belleza.

En otras partes de África, como Senegal, Mali y Benín, también se practican tatuajes y escarificaciones por motivos estéticos y rituales. En Asia, en lugares remotos de Myanmar y Tailandia, algunas tribus animistas también practican el tatuaje, y se cree que es necesario para acceder al paraíso en la vida después de la muerte.

En resumen, los Mbororo en Chad son parte de la comunidad Fulani, un grupo étnico nómada que practica tatuajes y escarificaciones como expresiones estéticas y rituales. Estas prácticas son características de muchas culturas africanas y algunas tribus asiáticas, y pueden tener significados tribales, de género, religiosos y medicinales.

In the village of Mbororo, situated in Chad in Central Africa, lives a community of around 250,000 members belonging to the Fulani ethnic group. The Fulani are a nomadic and animist subgroup residing in Central and Western Africa, being one of the largest ethnic groups of this kind in the world. The culture of the Mbororo is distinguished by their practice of tattoos and hair braiding as aesthetic expressions.

Scarification is a significant feature of African culture in which raised designs are created on the skin through cuts and the application of vegetable ash or other materials. These practices can be classified into four groups: tribal marks for ethnic differentiation, masculine scars to demonstrate valor and masculinity, feminine scarifications for aesthetic and erotic reasons, and for warding off illnesses through traditional healers.

Among the Mbororo, scarification and tattooing are integral to their nomadic lifestyle and have persisted due to their resistance to modernizing influences. Additionally, the Wodaabe group is mentioned within the Fulani, which has maintained their nomadic and cultural traditions, including tattoos and talismans to attract good luck and beauty.

In other parts of Africa, such as Senegal, Mali, and Benin, tattoos and scarifications are also practiced for aesthetic and ritualistic purposes. In Asia, in remote areas of Myanmar and Thailand, some animist tribes also engage in tattooing, with the belief that it’s necessary to access paradise in the afterlife.

In summary, the Mbororo in Chad are part of the Fulani community, a nomadic ethnic group that practices tattoos and scarifications as aesthetic and ritualistic expressions. These practices are characteristic of many African cultures and some Asian tribes, and can hold tribal, gender, religious, and medicinal meanings.

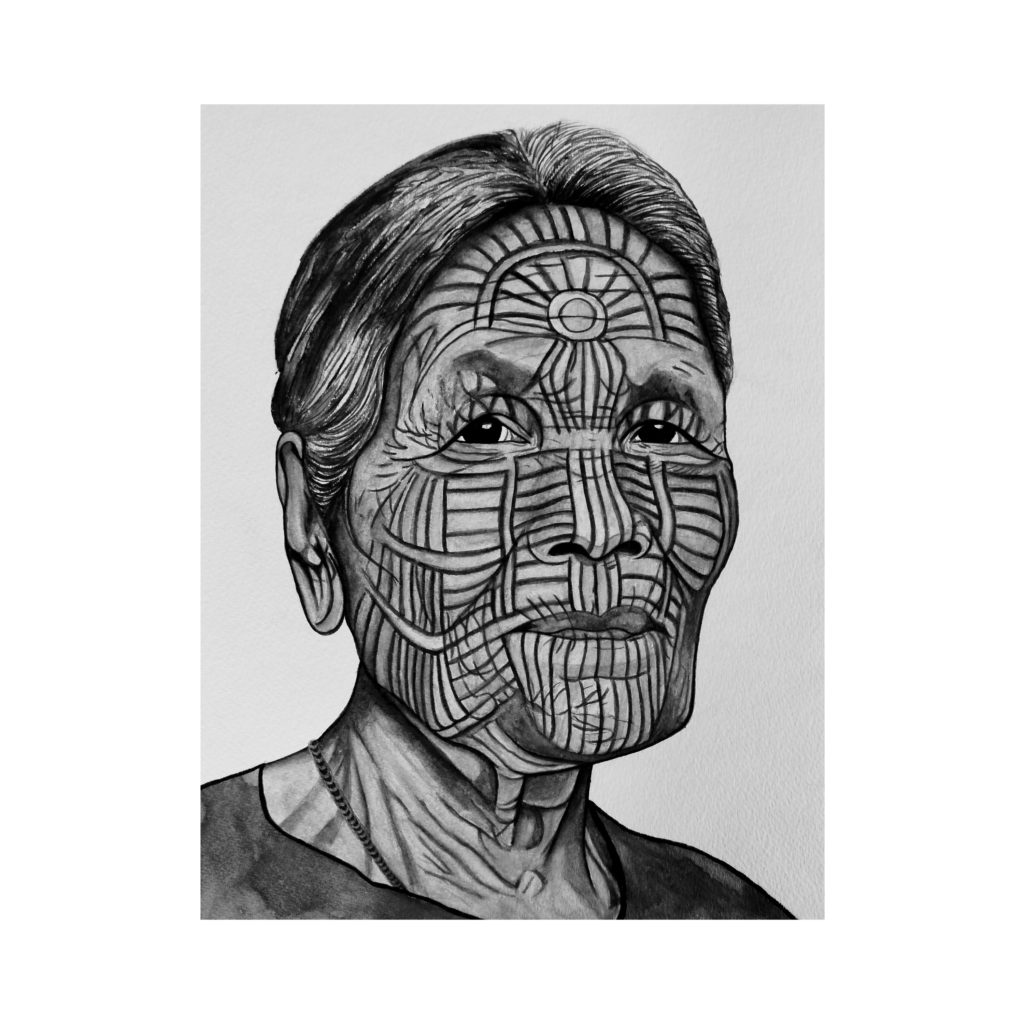

ACUARELA. Mujer tatuada de la tribu Chin. WHATERCOLOR. Woman tattoo of Tribe Chin. (Photo by bank of imagen )

El proceso de marcar sus caras se daba en niñas de siete a quince años y que duraba casi tres días, un proceso tan doloroso y largo que tenían que ser sostenidas y apoyadas por otras personas con el fin de poder aguantar de una vez todo el tatuaje facial. La hinchazón posterior era tal que las niñas no podían abrir los ojos y a veces ni siquiera podían hablar durante una semana. (La cara es una de las partes más sensibles del cuerpo debido a la alta concentración de los nervios y trabajar sobre una porción de la piel sin anestesia es extremadamente doloroso) Algunas lo hacían por sesiones y otras iban ‘adornando’ sus rasgos a lo largo de varios años. La tinta utilizada proviene de una planta especial que algunas tribus mezclaban con los riñones de un búfalo y era clavada en la piel con un instrumento parecido a una aguja de pino.

Las seis tribus Chin usan una variedad de tatuajes diferentes. El tatuaje puede consistir en una serie de líneas rectas, o bien puntos o círculos pequeños. También se da una combinación de ambos. Las mujeres M’uun son las más reconocibles, con grandes formas circulares de “P” o “D” en sus rostros y símbolos de “Y” en sus frentes. Las mujeres M’kaan tienen tatuajes de líneas en la frente y la barbilla. Las tribus Yin Du y Dai presentan largos tatuajes de líneas verticales en toda la cara, incluidos los párpados; similar al Nga Yah que tiene puntos además de líneas. La tribu Uppriu, una de las más difíciles de ver, tiene la cara completamente cubierta de puntos uno al lado de otro, con rostros casi ennegrecidos o de aspecto ceniciento debido a que están llenos de tatuajes

The process of marking their faces was done on girls aged seven to fifteen and lasted almost three days, a painful and lengthy procedure that required them to be held and supported by others in order to endure the entire facial tattooing at once. The swelling afterward was so severe that the girls couldn’t open their eyes and sometimes couldn’t even speak for a week. (The face is one of the most sensitive parts of the body due to the high concentration of nerves, and working on a section of the skin without anesthesia is extremely painful.) Some did it in sessions, while others gradually ‘decorated’ their features over several years. The ink used comes from a special plant that some tribes mixed with buffalo kidneys and was driven into the skin using a tool similar to a pine needle.

The six Chin tribes use a variety of different tattoos. The tattoo can consist of a series of straight lines, small dots, or circles. A combination of both is also seen. The M’uun women are the most recognizable, with large circular shapes resembling “P” or “D” on their faces and “Y” symbols on their foreheads. M’kaan women have line tattoos on their foreheads and chins. The Yin Du and Dai tribes exhibit long vertical line tattoos across their entire faces, including eyelids; similar to the Nga Yah tribe which features dots in addition to lines. The Uppriu tribe, one of the most difficult to see, has their faces entirely covered with closely-packed dots, resulting in faces that are almost blackened or ashen in appearance due to being covered in tattoos.

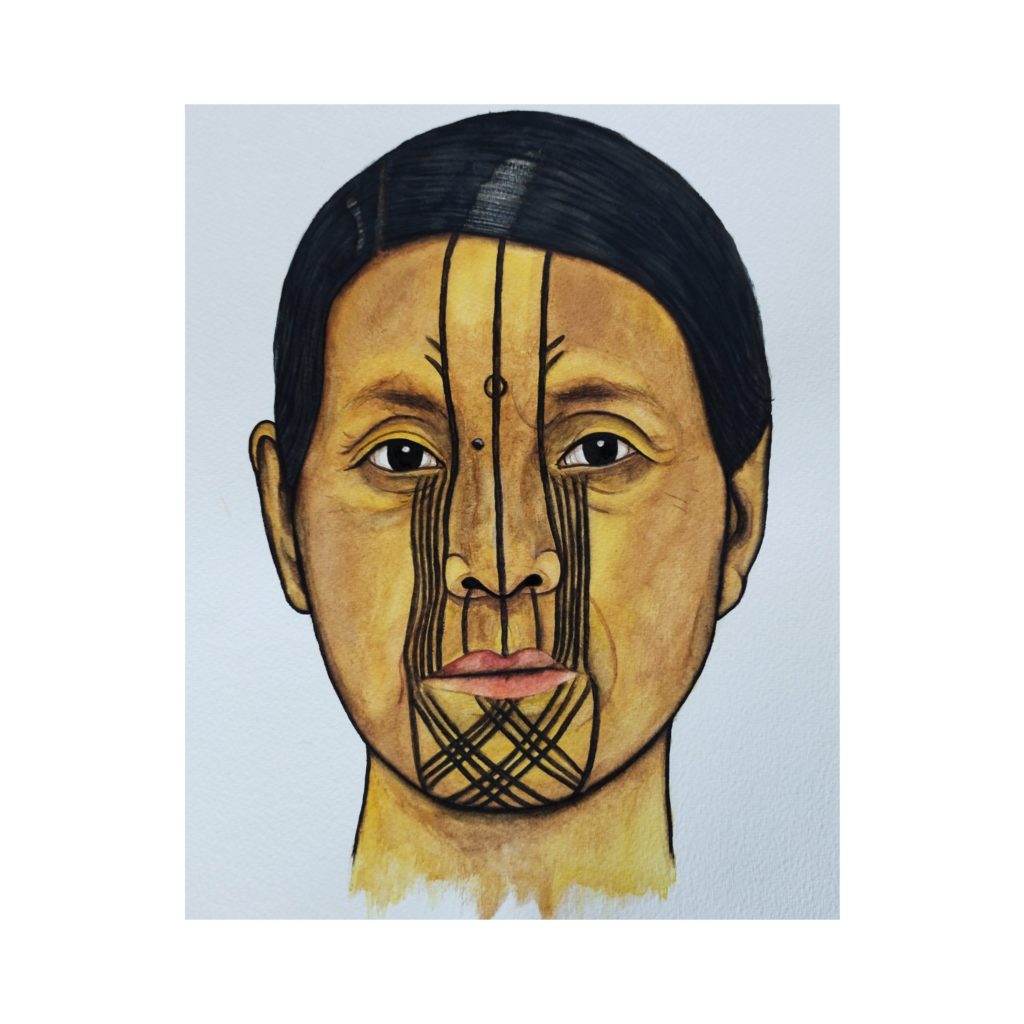

ACUARELA. Ta’kong, una mujer tatuada de Yonkon. WHATERCOLOR. Ta’kong, Woman tattoo of Yonkon. (Photo by Lars Krutak)

Yonkon Naga. la gente de Yonkon hace menos de trece años vivía en aldeas remotas cerca de la frontera de Myanmar con India. Pero con la falta de oportunidades educativas, empleo e instalaciones médicas en el hogar, muchos Yonkon se mudaron más cerca de Khamti en busca de nuevas vidas y futuros.

Las mujeres de Yonkon usan algunos de los tatuajes más distintivos entre los Naga de Myanmar. Descritas como “lágrimas”, se extienden desde los ojos hacia las comisuras de la boca. Los tatuajes de Yonkon fueron golpeados a mano en la piel con espinas de arbustos locales por mujeres tatuadoras. El pigmento del tatuaje se produjo a partir del jugo del árbol de laca. Se dice que el patrón protegía a las mujeres de los malos espíritus y que sus ancestros la reconocerían en el más allá. Antes de que cualquier hombre o mujer de Yonkon pueda ser tatuado, se ofrecen oraciones al santuario del espíritu guardián de la aldea por buena salud, larga vida y para que los tatuajes no se infecten.

Yonkon Naga. The people of Yonkon, less than thirteen years ago, lived in remote villages near the Myanmar-India border. However, due to the lack of educational opportunities, employment, and medical facilities at home, many Yonkon moved closer to Khamti in search of new lives and futures.

The women of Yonkon wear some of the most distinctive tattoos among the Naga of Myanmar. Described as “tears,” they stretch from the eyes to the corners of the mouth. Yonkon’s tattoos were hand-tapped into the skin using thorned branches by female tattooists. The tattoo pigment was derived from the juice of the lacquer tree. The pattern is said to protect women from evil spirits and to be recognized by their ancestors in the afterlife. Before any Yonkon man or woman can be tattooed, prayers are offered to the village guardian spirit shrine for good health, long life, and to prevent the tattoos from getting infected